Thousands of microscopic seeds from the Striga weed lurk dormant in every handful of arable soil. As soon as the time is right, they begin to germinate. They send their roots out to the nearest maize or millet plant, penetrate its roots and deprive it of water and nutrients, thus stunting the plant’s growth. The weed, meanwhile, thrives: it forms beautiful purple flowers and eagerly produces seeds for the next generation.

In East Africa’s push-pull fields, however, the dreaded Striga has an opponent superior in terms of both sophistication and power: Desmodium. The legume relies on tactical confusion and an arsenal of chemical weapons that it emits from its roots. It attacks the weeds underground with two combinations of different plant chemical compounds. The first lures the Striga from its dormancy by stimulating its seeds to germinate. The second attacks the sprouting roots and thus prevents the parasite from docking onto the maize plant. The Striga has no chance: it dies before it can grow and reproduce. Desmodium can free arable soils from the devastating Striga weed within four years, thus preventing massive harvest losses over the long term.

Desmodium and elephant grasses protect crops and the soil

The legumes present even more advantages. Thanks to the bacteria in their root nodules, they bind nitrogen from the air. Through this natural fertilization, they help build and maintain soil fertility. As a permanent ground cover, they also effectively protect the soil from erosion and drying out. Above the surface, Desmodium’s scent discourages insects, such as the harmful stemborer moth, from laying eggs on the crops. In this way, maize and sorghum millet are spared from the voracious larvae that would otherwise hatch on them, bore into their stems and destroy them from the inside.

But that’s not all: in push-pull fields, other companion plants are cultivated around the fields that help keep pests at bay through volatile messenger substances. While maize or millet unwittingly attract stemborer moths with their scent, especially at night, grasses such as elephant grass at the edge of the field emit their scent earlier at dusk. In this way, they lure the harmful insects to themselves rather than to the field. The moths fly to the edge of the field and lay their eggs on the sticky leaves of the grasses, to which the offspring adhere and perish.

Plants send SOS signals

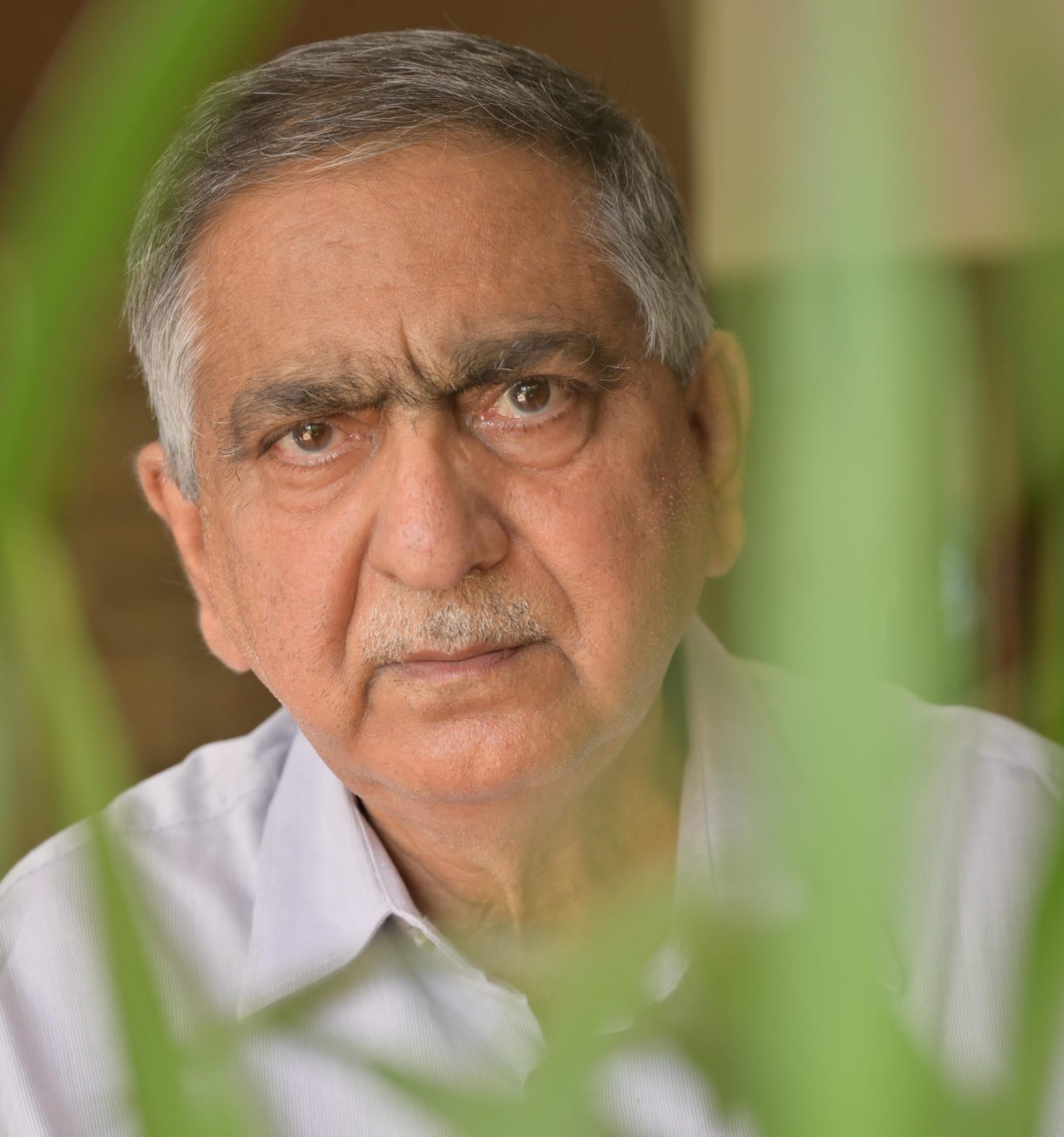

The ingenious cultivation method relies on plants being able to communicate with both pests and beneficial insects, and with other plants. “Many wild grass species have developed clever strategies to protect themselves and their neighbouring plants from pests”, explains the father of the push-pull method, Professor Zeyaur Khan of the International Centre of Insect Physiology and Ecology (icipe) at the Kenyan research station in Mbita on Lake Victoria.

“Molasses grass has the special ability to use chemical SOS signals to summon pests’ natural enemies”, explains the entomologist. In the case of the stemborer, the natural enemies are parasitic ichneumon wasps. These wasps lay their eggs in the moth larvae, which the wasp larvae eat once they hatch. “The grasses can even warn their plant neighbours of pest attacks. Those neighbors then send out their own SOS signals”, says Khan. That is not all, the scientist adds: “Unlike modern hybrid maize varieties, old traditional species are also able to receive these messages and can learn to send out signals themselves.”

“Soil is the mother of plants”

Despite all the scientifically sophisticated methods he propagates, in Professor Khan’s regular exchanges with farmers he always returns to the basis of all successful agriculture: “The soil is the mother of your plants”, he always tells them. “If you have healthy soil, you will have healthy plants that produce more. Only by doing so can you preserve your land for your children.”

Hats off to you, professor!

For the last 30 years, entomologist Professor Zeyaur Khan has been tirelessly developing the push-pull method he developed and adapting it to ever new challenges – such as the consequences of climate change or emerging pests. For example, he and his team have successfully determined the chemical composition of messenger substances, giving us a better understanding of communication between plants. The award-winning researcher and long-standing Biovision project partner deserves great recognition and gratitude for his extremely valuable work in the service of African smallholder farmers.

Biovision has been supporting Prof Khan and his team for 20 years to further develop and spread the push-pull method, which can double or even triple crop yields. It has already helped many thousands of smallholder farmers get a stronger hold on their livelihoods.