White sandy beaches lined with coconut palms, mud-hut settlements amid lush tropical vegetation – the scenery in Kwale, at the southernmost tip of Kenya, is breathtaking. But the idyllic scene is deceptive: the state is one of the poorest regions in the country. Income opportunities are scarce for villagers, access to health services is limited, and the number of cases of malaria and other vector-borne diseases – infections transmitted from insects and ticks – is high.

“We get stung every day,” says Mariam Shee Mwabami. She sits in front of her mud house with her three-month-old daughter on her lap. Every sting and every bite pose a risk of infection. For children and the elderly in particular, tropical diseases like malaria, Rift Valley fever, and dengue fever pose a deadly danger.

A long march to the hospital

The possibility of illness creates an additional economic risk for people already struggling with an extraordinary drought and increased food prices. For example, Asha Ali (68) lives off home-grown corn and cassava roots and the meagre income that she earns from basket weaving. Falling ill with malaria last year threw her household off balance: the treatment cost of 500 Kenyan shillings (KES) per day (4 Swiss Francs) exceeded her budget, and she had to walk several hours to the hospital. “By the time I got back home, the day was over,” she says, “and after that it was several days before I could return to work.”

An additional risk of infection comes from cows, which live close to people. They attract vectors: animals that transmit diseases from one animal to another. This is precisely where icipe (the International Centre of Insect Physiology and Ecology), a longstanding project partner of Biovision in Kenya, has an innovative solution in which the animals act as a kind of decoy, attracting insects to them. A newly developed biopesticide then helps to eliminate the insects – a benefit to animals and humans alike.

Fewer vectors mean a lower risk of infection for humans. Additionally, healthier animals have a positive effect on smallholder families’ incomes. The principle of addressing human, animal, plant, and environmental health as a whole is called “One Health” – an approach that Biovision is pursuing in more and more projects.

Researchers from the village

Early Monday morning in front of Mariam Shee Mwabami’s mud hut, two young men wearing beige vests with icipe lettering and the Biovision logo examine an insect trap behind the house. Akiba Bakari Mvumoni, 23, drips a solution onto a mosquito caught in a sticky trap, and his partner, Majaliwa Backari Zengwa, 26, carefully detaches it with tweezers. Zengwa drops the mosquito into a plastic vial filled with absorbent cotton and a solution that kills and preserves the insects in seconds.

Mvumoni and Zengwa are known as CORP: Community-Own Resource Persons. They are responsible for setting up various traps and collecting the insects, which are then identified and counted in the laboratory of icipe insect researcher Paul Oma. Once the study is completed in the spring of 2023, it will become clear whether spraying the cows with the biopesticide actually decreases the number of vectors.

The fact that the study is being conducted by people from the village communities – those who will benefit – is part of a new participatory approach. This is the first time that icipe has applied this approach on a large scale, as project manager Dr. Margaret Mendi Njoroge emphasizes. She is enthusiastic about the response of the villagers and their commitment and already concludes: “Participatory research is the way of the future.” (See interview at the bottom.)

Income and knowledge

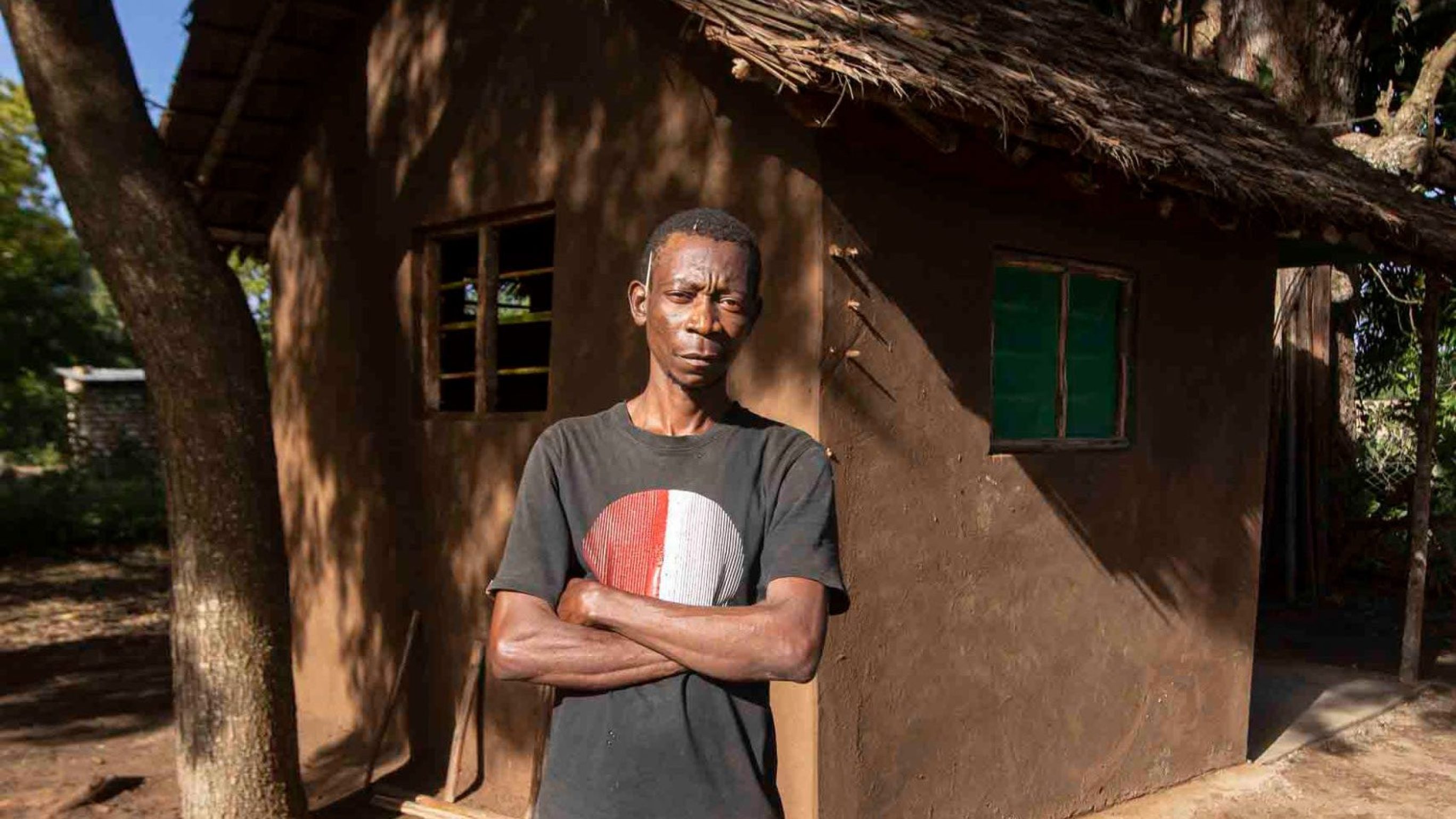

Salim Athman Mwinyihaji is also enthusiastic. The 32-year-old is the father of two children and the breadwinner for a household of seven, including his mother and younger relatives. The CORP job, for which he was nominated by the village head and which he got after an interview, means a lot to him. He says that he got it even though, unlike others in the village, he was only able to complete elementary school because there was no money at home. The job, as his mother emphasizes, gives him pride and dignity. He also earns more than in his previous job driving a motorcycle cab.

It’s very similar for 23-year-old Mohammed Rashid. For him, too, the income from his assistant’s job in the project is important. He is an orphan and is building his own house, in which he already lives. The roof is only rudimentary, so when it rains, he squeezes into a corner of the house where the rain does not penetrate. Similar to Salim Athman Mwinyihaji, the job is important to Rashid on another level. This becomes apparent at the community meeting in Zigira – a meeting of the inhabitants of his village with the project managers from icipe.

Rashid stands in line with the researchers and answers the villagers’ questions: How does this trap work, how does that one work? Does malaria develop in mosquitoes or are they only carriers? The people have many questions. Project leader Margaret Mendi Njoroge says, “A crucial part of the project is education. We provide the project participants with elementary knowledge about vector-borne diseases.” For example, they had a community meeting with the villagers to clarify that larvae are mosquitoes in their early stages and not, as some thought, another type of insect that poses no risk of infection.

Pesticide without side effects

Another essential job in the study is that of “intervention attendants,” who support the cattle farmers in carefully spraying cows and cattle. This is done with a fungus-based solution that was developed and produced by a Kenyan company in collaboration with icipe. The solution has several major advantages over synthetic pesticides: the vectors barely develop any resistance; it is harmless to humans, animals, and the environment; and it offers the prospect of decimating the vector populations.

So how well does prophylaxis, which has been successful in the laboratory, work in practice? Margaret Mendi Njoroge is optimistic based on how well the project has gone so far, but she awaits the publication of the results next spring for a final verdict. CORP scientist Salim Athman Mwinyihaji says the same thing when villagers ask him about it. However, if you ask the farmers who spray their animals, you get a clear answer: after a few days, the ticks fall off the cows. But in contrast to spraying with poison, the infestation does not soon recur.

Confidence is high that the icipe team, as research pioneers, have discovered a solution that will sustainably improve the lives of people in scenic Kwale County and beyond.

Find out more about the project

People who live and work with animals are particularly at risk of contracting malaria or sleeping sickness. This project promotes integrated vector management as a multifaceted and sustainable method of disease prevention and control.

Three questions for

Dr Margaret Mendi Njoroge

What is your experience with participatory research?

Collaborating closely with the village communities meant, first of all, that we had to learn to communicate better. The people involved have never done science in their lives, yet we expect them to perform key tasks in a research project. Surprisingly, they do it much better than I ever thought possible.

How do the people involved benefit from the project?

First and foremost, in the form of education: they learn what it takes to find a solution. Second, they feel heard. That may sound like an abstract gain, but it is important. And finally, this project creates urgently needed jobs. I would emphasize this point less strongly than the education, however, because education empowers people more. Money is fleeting, but knowledge remains for life.

How do you envision the future?

For researchers, the participatory approach is simply the way of the future. On the one hand, the people affected greatly appreciate their close involvement; on the other hand, it is crucial to the success of the developed solution. After all, they are the ones who will use it in the end.

About Dr Margaret Mendi Njoroge

Dr Margaret Mendi Njoroge, researcher at our project partner icipe in Kenya, is leading the research project. For her, there is no doubt: “Participation is the way into the future”.