People’s health takes priority in our projects. Due to the coronavirus pandemic, we have therefore cancelled all project visits to East Africa by Biovision staff for the current year. But I still have a very clear recollection of a visit on 4 May 2017 to meet Bishar Dulo in Boji, a village in the semi-arid expanses of land north-east of Mount Kenya.

The dominant local colour is ochre – the colour of the sand. White limestone shines through in between, along with greenery from thorny bushes and trees. It is noon and the village is dozing in the oppressive heat. The winding path to Bishar Dulo’s house leads me past oblong mud houses on spacious plots of land.

The widow and mother of six from the Borana community has dressed up for our conversation, and welcomes me with one of her grandchildren in the shade of a tree. Three of her adult sons are cattle herders and often have to take their herds a long way from the village in a constant search for water and pasture. And that is becoming increasingly difficult, says Bishar Dulo.

Recently, however, the area has been hit by extreme drought every two to three years. That is why her sons are often away for long periods. And since herdsmen earn very little, she not only has to provide for four grandchildren, but also has to support her sons.

“It used to be much easier for me. My husband died seven years ago. He was the head of the family and we shared the responsibility,” she explains. At that time they had more goats to sell in the town. That was enough for them to live on. “Now there are only 15 animals in my herd, and my income is very low.”

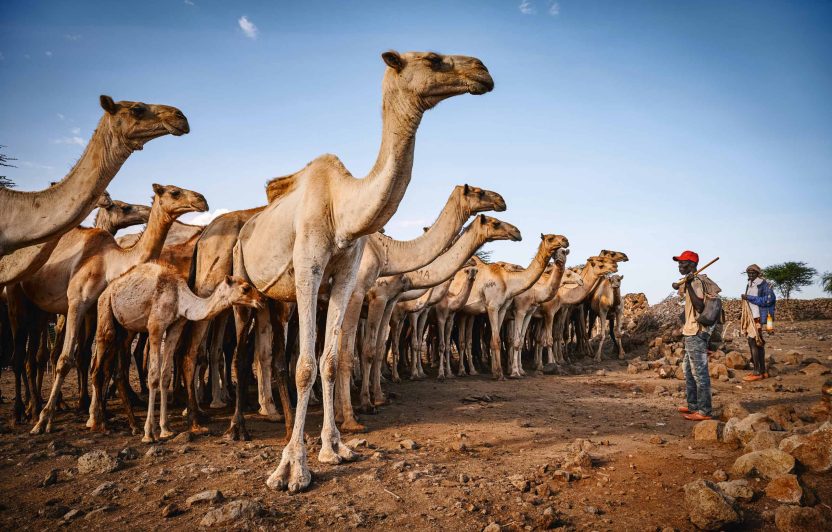

On account of her difficult situation, Bishar Dulo was selected by the village community as a camel owner for the Biovision project “Camels for Drought Areas”. Camels are much better adapted to drought than small livestock or cattle. This helps make farmers more resistant to the effects of climate change. Once the mare gives birth to a foal, Bishar Dulo will have milk for her own use and for sale. “If the baby is a female, I will continue breeding with her. If it’s a male, I will sell him,” she says with anticipation.

When I ask her about the greatest wish she would fulfil with the income, she does not hesitate to answer: “I’d like a house with a tiled roof,” she says confidently with a smile. When I retire to a hot room under a tin roof in the evening, I can relate to Bishar Dulo’s wish very well. And when coronavirus finally permits travel again, I will go back there to see what has become of her dream.