Do you know what is the most dangerous animal in the world? Is it a poisonous snake, a great white shark or a grizzly? Far from it: mosquitoes kill more than half a million people every year by transmitting dangerous diseases, most of all malaria.

This is why combating malarial mosquitoes is a high priority for the international community. Often, attempts are made to encourage individual measures, such as using impregnated bed nets or spraying insecticides as thoroughly as possible. These approaches have saved many lives: worldwide, the death rate has fallen by 60 % since the turn of the millennium, and 20 countries have been able to eliminate the disease completely. With the increasing resistance of mosquitoes, however, these individual measures are reaching their limits. New instruments and an integrated approach are needed to achieve the planned eradication of malaria in the remaining 86 countries of the world.

Biovision relies on a holistic method known as Integrated Vector Management (IVM), which combines multiple measures for mosquito control (see green box). The longstanding “Stop Malaria” project implemented these measures at three locations in Kenya and Ethiopia. The local partner organizations, the International Centre of Insect Physiology and Ecology (icipe) and the Kenya Medical Research Institute (KEMRI) supervised the project on site. Ultimately, our aim was to prove scientifically that IVM works. But does it really?

Adapting IVM measures to each location

“It depends on the conditions at the specific location,” says Professor Charles Mbogo, project manager at KEMRI. “In Malindi, we have seen an impressive decrease in malaria cases over the course of the project. ”But the number of cases has also fallen elsewhere (see figure). Therefore, randomized controlled trials (RCT) were needed to assess the method’s effectiveness. The result: IVM, and in particular larval control through environmentally-friendly Bti (Bacillus thuring iensis israelensis), works best in high-density populations at a manageable number of breeding sites. This is the context in and around Malindi, where malaria has been largely reduced. In areas that remain highly infested such as Nyabondo on Lake Victoria, the second project site in Kenya, larval control was less effective. There, sealing houses to prevent mosquitoes from entering proved to be an effective measure.

IVM is expanding its reach

These findings are important for further targeting IVM promotion at political level. Kenya and Tanzania have already achieved initial success: national governments are financing larvae control in larger areas. The experience gained there, as well as manuals and school curricula from the Biovision projects, are now proving to be very helpful. Biovision is also helping the governments of Namibia and Uganda to develop and implement national roadmaps for IVM measures through the UN Environ ment Programme.

Further developing IVM

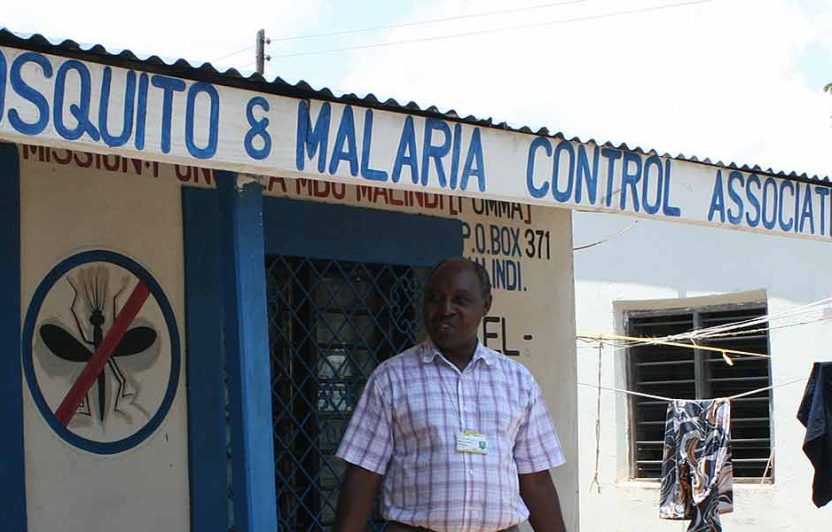

The long-standing model project “Stop Malaria” ended in 2019, but local structures such as the PUMMA Mosquito Scouts Association remain in place. The IVM concept will be consistently used by Biovision and icipe in the new project “Innovative disease prevention in animals and humans”. In this project, a new method will be added to the IVM toolbox. Whereas our measures have so far concentrated on malaria control and hence on humans, cattle are now also being included in the project scope. By adopting an integrated approach, the expanded method will kill two birds with one stone, as it were. Cows that serve as bait to bloodsucking Anopheles mosquitoes will be sprayed with a bioinsecticide, thus eliminating the Anopheles mosquitoes and reducing the entire mosquito population. Other parasitic bloodsuckers that spread dangerous animal diseases, such as tsetse flies and ticks, will be decimated in the process. The project is still in its early stages. As it is being developed, people in the affected communities will be closely involved so that the method can be adapted to their needs.

Danger from the coronavirus

A large field trial was intended to be started this year to check whether the new method would bring the expected synergies. It will take some time before the disease is eradicated, but the end is in sight. Malaria could be defeated outside of Africa by 2030. Experts believe global eradication is possible by 2050. But East Africa is currently facing a new challenge: the coronavirus pandemic has reached the continent. There is growing concern that the lockdown will also affect malaria treatment and thus cause much greater damage than the coronavirus itself. Ultimately, sustainably preventing pre-existing and familiar diseases should be more important now than ever.

Comment:

We need political will

The holistic approach of Integrated Vector Management (IVM) works for malaria control. This was clearly shown by the “Stop Malaria” project supported by Biovision since 2005. When the project began, about 40 % of people in the Malindi Subcounty were infected with malaria. Today, this prevalence is only about 3–5 %. Similarly, mosquito populations were reduced by about 75 % – these numbers speak for themselves!

Integrated Vector Management also has a positive effect on viral diseases that are transmitted by mosquitoes, for example dengue, yellow fever, chikungunya and elephantiasis. These infections have also declined in the project area, which is encouraging.

Now it is time for decision-makers at county and national level to adopt the IVM strategy for malaria control and allocate the necessary resources. However, this is very hard to achieve. There are still potent at work, seeking to discredit the idea of tedious multi-stakeholder collaboration and community participation and instead promoting individual interventions with synthetic insecticides. The science clearly shows the added value of IVM. We now need to bring these results to the policymakers to obtain the political will necessary for such an integrated approach.